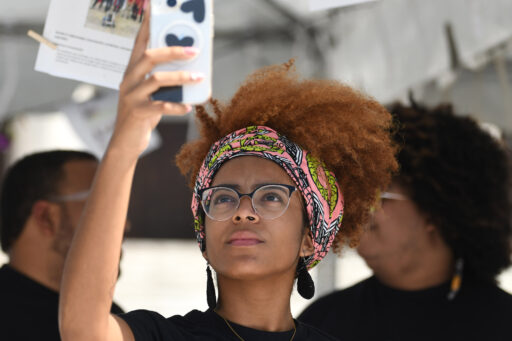

Photo by Herminio Rodríguez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

The most important initiative against gentrification in Chicago came from the Puerto Ricans agenda in the city. In February of this year, the government of Illinois designated the Chicago-Puerto Rico Town, one of 10 cultural districts that are eligible to receive funds to address the needs of the area, foster economic development and help communities preserve their cultural identities.

The stories of Puerto Rican politicians Jessie Fuentes and Cristina Pacione Zayas are the stories of wanting to stay in that neighborhood. Both are the result of community work by the Puerto Rican Cultural Center of Chicago, founded more than 50 years ago. At every opportunity, they talk about the initiatives created from there and that give life to Paseo Boricua, in Humboldt Park, a neighborhood that has been the heart of the Puerto Rican community in the city since the migratory waves began to establish themselves in the area in the 1960s and 1970s.

Jessie Fuentes is the first queer Latina to be elected to the Chicago City Council and is a graduate of the iconic Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos Puerto Rican High School, founded in the basement of a Chicago church in 1972 as La Escuelita Puertorriqueña (The Puerto Rican School).

Photo by Gerardo Mora | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

She was born and raised in Humboldt Park. Her mother was Puerto Rican and her father, a “marielito,” from the group of Cuban immigrants who left the port of Mariel in Cuba in 1980 to go to the United States, after a diplomatic agreement between both countries. For most of her childhood and adolescence, her father was in prison. At the same time, her mother was struggling with drug addiction. Her family situation was a tough battle to manage emotionally and socially. She describes herself as a girl and young woman who got into a lot of trouble. She attended seven elementary schools and three high schools.

“It was de Pedro Albizu Campos School, it was the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, the Puerto Rican community, that, to be quite honest, saved my life. And I chose to live my life paying that forward.”

That’s why, she says, she became an activist, an educator and, in 2022, she decided to run for the position of Alderwoman of 26th Ward, where the Paseo Boricua and the Puerto Rican Cultural Center are located.

“It’s not enough to be on the outside. Right? In mobilizing and organizing. But if you don’t have someone on the inside that’s going to listen to the movement on the outside and play the inside game, then there’s only so far you can go.”

And Fuentes is confident in her new power to push legislation and pursue changes in systems. “We can start by bringing community organization to the government.”

One of her most recent achievements has been the adoption of the minimum wage for restaurant workers, who, as in Puerto Rico, subsisted on a sub salary that was often not enough even with tips.

When Fuentes ran, she was not alone. Progressive candidates ran throughout the city and today 19 of them are members on the City Council, which has 50 aldermen and alderwomen.

“To have the privilege to now represent the very same community that saved my life and to think that we can create legislation that’s going to save thousands of lives is probably the greatest honor,” Fuentes said.

Photo by Herminio Rodríguez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Agenda Against Gentrification

Fuentes learned the history of how the Puerto Rican community in Chicago has been continually displaced since the beginning of migration from Puerto Rico. From LaSalle and Clark to Lincoln Park to Lakeview to Wicker Park to West Town. And now, in Humboldt Park, the threats continue.

“The movement of gentrification has unfortunately contributed to the historical and generational trauma that Puerto Ricans are facing in Chicago,” she said.

Making more housing available, opportunities to purchase affordable property, housing cooperatives and having real conversations about public housing in the face of the large number of homeless people are part of her agenda as an alderwoman.

Another priority for Fuentes is economic development to create stability for families, as well as affordable housing. It is also a way to confront the displacement that has been promoted by the large corporations that have established themselves in the area: they don’t pay fair wages and don’t provide health insurance or decent health services to their workers.

Photo by Gerardo Mora | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

Cultural Districts as an Idea Against Gentrification in Chicago

Cristina Pacione Zayas is the Chief of Staff for the Mayor of Chicago, Brandon Johnson, and is also a product of the community work carried out by the Puerto Rican Cultural Center on Paseo Boricua. She began in this position last month, after having being Deputy Chief of Staff since Johnson became mayor in 2023. In addition, she was a senator for the Democratic Party in the state of Illinois, between 2020 and 2023.

Pacione Zayas said that when she started getting involved in anti-gentrification work, the phenomenon was already occurring in the adjacent Humboldt Park neighborhood, where the Puerto Rican Cultural Center is located. The community, established there decades ago, has presented significant resistance against displacement.

When asked what began to displace Latino families in the area, Pacione Zayas explains: “We have not had a living wage in our state. And obviously the change from an industrial to a more service-based kind of sector, that changes things,” she mentions as some of the external factors.

She said although the nearby schools are not considered the best, the location, architecture and easy access to highways and public transportation, which can get someone to the city center in about 15 minutes, have made the area attractive for people with greater purchasing power.

“That has pushed out Latinos, because then the rent goes up, the property taxes go up, and a lot of the original residents can no longer afford it because we’re still working class. You know, all those things go up, yet our wages are still down here,” she said.

The Legislation of the Cultural Districts

Time before Pacione Zayas came to the Senate and Fuentes to the position of Alderwoman, the Agenda Puertorriqueña de Chicago, a nonprofit organization made up of dozens of other organizations, was already developing work focused on combating gentrification and identifying political mechanisms to stabilize the Puerto Rican community in Chicago, honoring their identity.

Photo by Herminio Rodríguez | Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

They explored different models. First, they thought about creating special tax districts. Geographic areas would be designated in which development would come from a special tax. They knew it would be tough to get support for legislation like that.

Then they came up with another idea.

“Let’s create a state designated cultural district where the state would recognize a unique geography. It could be a community, it could be, you know, a city, it could be a county, it could be a couple counties. The point is it would be something that has a cultural identity that’s at risk of erasure or the residents are at risk of being displaced,” said Pacione Zayas.

The idea is that by getting state recognition as a “cultural district,” these areas are provided with special protection, allowing them to have an advantage when applying for federal, state, and municipal funds.

“Now, what we want to do is get funds to acquire property, to build up cultural institutions, to anchor them fully, to continue to make this sort of an economic development initiative, but not just for the sake of capitalism, but for the sake of preservation of our communities,” Pacione Zayas said.

The group drafted legislation that was introduced in 2020 but was unsuccessful. After reaching the state legislative assembly at the end of that year, the then-new legislator Pacione Zayas presented it as her first proposal.

The now alderwoman Jessie Fuentes, who at that time had not ventured into electoral politics, was one of the people from Agenda Puertorriqueña leadership who came to the Senate to talk about the importance of the Illinois Senate Bill 1833.

“I think the bill captivated the imagination of our colleagues because across Illinois, we do have so many distinct, unique cultural, historic kinds of enclaves. And I think people really resonated with the preservation and conservation of those communities and understood that the threat of displacement and gentrification isn’t just unique to Chicago, it is across the state,” Pacione Zayas recalls.

The legislation passed with bipartisan support. On the last day of October 2022, Hispanic Heritage Month, Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the bill into law during a celebration at the National Museum of Puerto Rican Art and Culture. On June 1, the community will name its cultural district Barrio Borikén.

Over the course of 10 years, the state can designate up to 15 cultural districts, which will have access to separate funds for their development, which should serve as seed money aimed at sustainability. Governor J.B. Pritzker has already designated 10: North First Street Cultural District, Bronzeville District, Chinatown, Clark Street/Camino Clark, Mahalia Jackson 79th Street Cultural District, Little Village, South Chicago Cultural District, Puerto Rico Town; and in Springfield, the Central East Cultural District and The Southtown Cultural District. A $3 million allocation has already been set aside to distribute among the designated districts.

What the Puerto Rican community has achieved in Chicago, specifically on Paseo Boricua, is unique because it has been overseen by a movement that believes in the decolonization of Puerto Rico. The possibility of remaining where one has been for generations, of having access to decent housing and education, which fosters political awareness; the creation of local companies, all are forms of decolonization, even within the United States.

“Before we think about the decolonization of Puerto Rico, we must be able to practice that in our own communities. And so, the self-determination, self-reliance, and self-actualization of Puerto Ricans in Chicago, particularly in Humboldt Park, in Paseo Boricua, is the very framework in which we function,” says Fuentes, recognizing that displacement is a common element among Puerto Ricans in Chicago and those who live on the island.

“We have to be able to also own our land.”